Hace poco tuve el placer de conocer a Lucía Solís, experta en fermentación muy metida en el sector del vino. Lucía ha estado trabajando en el mundo del café de especialidad los últimos tres años como “diseñadora de fermentación para cafés”: ayuda a las estaciones de beneficio a racionalizar, mejorar y personalizar sus procesos de fermentación.

La visión antigua (y actual) de la fermentación es que no ofrece ninguna oportunidad para mejorar el sabor, solo riesgos. La nueva visión (la de Lucía) recomienda no dejar la fermentación al azar sino gestionarla de una manera que ayude a mejorar el producto final mientras se reduce el riesgo de empeorar los lotes por debajo del nivel habitual.

Sorprendentemente, algunos compradores de café en verde han criticado la labor de Lucía y parecen asustados por el hecho de que el diseño intencionado de la fermentación reduzca la diversidad de sabores de café disponibles o “estropee” el café de alguna forma. Numerosas ideas innovadoras asustan un poco al principio, pero yo apoyaré cualquier propuesta que prometa proteger a los caficultores ante riesgos, suponga un pequeño paso para que el beneficio sea más predecible y aporte al responsable de dicho proceso una nueva herramienta.Os animo a leer lo que tiene que decir Lucía y a decidir por vosotros mismos. Me encantaría saber vuestra opinión.

Scott

Por Lucía Solís

Mi trabajo como enóloga y ahora como responsable de fermentación de café se centra en una verdad sencilla: la fermentación genera componentes químicos con características sensoriales.

Mi intención inicial era centrarme en los microbios por mi experiencia como enóloga. Cursé un grado en Viticultura y Enología en UC Davis y trabajé durante casi una década en bodegas del valle del Napa (California) antes de que mi experiencia en microbiología y fermentación me llevara al mundo del café.

Actualmente, viajo a estaciones de beneficio y fincas de café de Centroamérica y Sudamérica, donde trabajo directamente con productores para cambiar su forma de procesar el café.

Los tostadores pueden proporcionar sabores diversos ofreciendo cafés de diferentes lugares del mundo. Esta práctica enfatiza las diferencias regionales que muestran el efecto de la geografía, pero minimiza el papel del procesamiento tras la cosecha en el desarrollo del sabor.

La mayoría de las diferencias entre cafés se suelen atribuir a varietal, clima y condiciones de cultivo, pero es normal pasar por alto la contribución de los microbios.

Los pequeñísimos microbios (levaduras y bacterias) que transforman la cereza de café en pergamino tienen la capacidad de afectar enormemente al sabor. El proceso de convertir la cereza en café verde listo para tostar incluye varios pasos. En cada uno se puede influir en el sabor y la calidad.

El proceso de convertir la cereza en café verde listo para tostar incluye varios pasos. En cada uno se puede influir en el sabor y la calidad.

Texto del diagrama:

Cherry: cereza / Pulp: pulpa / Full removal: retirada completa / No removal: sin retirada / Partial removal: retirada parcial / Dry process: vía seca / Wet process: vía húmeda / Tank: depósito / No tank: sin depósito / Dry fermentation: fermentación en seco / Submerged fermentation: fermentación con inmersión / Wash: lavar / Natural: natural / Pulped natural (honey): Honey / Washed: lavado / Mechanical demucilagination: Retirada mecánica del mucílago / Dry: Seco

Contamos únicamente con un puñado de términos para describir los métodos de beneficio, por ejemplo, lavado, vía húmeda, honey o natural, pero cada una de estas palabras puede englobar pasos muy diferentes y complejos. Dichos pasos y el tiempo que transcurre en lo que se describiría como proceso “lavado” varían enormemente en función del clima, altitud, varietal, madurez, diseño del depósito e infinidad de variables más que afectan a la cinética de la fermentación.

Un café podría pasar entre 8 y 72 horas en contacto con el mucílago (fermentación) antes de lavarse. El término “totalmente lavado” no tiene por qué implicar que un café se haya fermentado. Aunque sepas con certeza que esto ha sucedido, un café fermentado en seco durante 8 horas probablemente sabrá diferente a uno fermentado bajo el agua durante 40 horas; como si comparamos uno fermentado a 700 m de altitud (msnm) a 26°C con otro fermentado a 1500 msnm a 12°C o uno fermentado en madera con otro en depósitos cerámicos, etc.No solo las palabras que usamos para describir el proceso son insuficientemente específicas. Además, se sabe poco de los efectos en el sabor de los diferentes pasos de los procesos o de los microbios que intervienen durante dichos pasos. En eso se centra mi trabajo.

Para poder cambiar la manera de procesar el café físicamente destacando los efectos de los microbios presentes, tuve que actualizar la definición de los productores del término “fermentación”. He estado intentando enseñar a los productores los efectos en el sabor de diferentes cepas de levaduras y bacterias, pero no llegaba a ningún lado. Al final, me di cuenta de que poca gente era consciente del valor de la fermentación en un primer momento.

Usaba la palabra “fermentación” para describir un proceso metabólico a través del cual las levaduras y bacterias transforman los azúcares en energía y compuestos de sabor. Aunque la definición más habitual en el caso del café es “el paso en el que el café con la pulpa reposa en un depósito hasta que el mucílago se desprende”. Fue como intentar enseñar a los tostadores a tostar con un RoR descendente y darse cuenta de que no entienden el efecto del grosor del sensor en la curva.En la industria vinícola, la fermentación se estudia ampliamente porque se trata de un paso necesario a la hora de elaborar vino: sin ella no se consigue el producto. Me di cuenta de que en el sector del café se usaba el mismo término, pero este tenía un significado muy diferente para casi todas las personas con las que hablaba. Creo que el motivo principal de esta discrepancia es que la “fermentación” es opcional en el café; se trata, simplemente, de un método para aislar la semilla de una cereza.

Además de ser opcional, no está limitada a un único proceso como se solía pensar. La fermentación no sucede únicamente en depósitos con los cafés de vía húmeda/lavados; también está presente en los procesos honey y de vía seca/natural. En todos los procesos en los que existe fermentación, hay una opción de influir en el sabor. La fermentación empieza en el momento en el que los microbios, que existen virtualmente en todas las superficies, encuentran un punto de entrada a la fruta. La posibilidad de la fermentación se da en cuanto la fruta se recoge o cuando hay daño en la piel (jugo expuesto) mientras la cereza aún sigue en el árbol.

Para gestionar el riesgo de fermentación espontánea en la elaboración de vino, hay bodegas donde se vendimia de noche (en el momento más frío de la jornada, para ralentizar la acción microbiana). Las uvas se rocían con dióxido de azufre para limitar la población de levaduras salvajes procedentes de la tierra o bien se almacenan en hielo seco hasta que estén listas para empezar la fermentación con microbios conocidos y seleccionados.

La fermentación es un proceso natural que tiene lugar sin intervención humana. Los productores de vino deciden activamente si se arriesgan con una fermentación espontánea o eligen los microbios y controlan el proceso. Aunque opten por usar levadura salvaje y no comercial, están tomando una decisión que afecta activamente al sabor. La mayoría de los productores comerciales de productos fermentados (vino, pan, queso, cerveza, chocolate) inoculan la fermentación. Esto es poco común en la industria del café porque el foco se ha puesto en reducir los riesgos en el procesamiento, y los beneficios del punto anterior no se han entendido demasiado bien.

El vino, el chocolate, el queso, la cerveza y el pan, varios productos de otras industrias que aprovechan la acción de los microbios para alcanzar los resultados deseados.

Things that are fermented on purpose: Alimentos que se fermentan a propósito

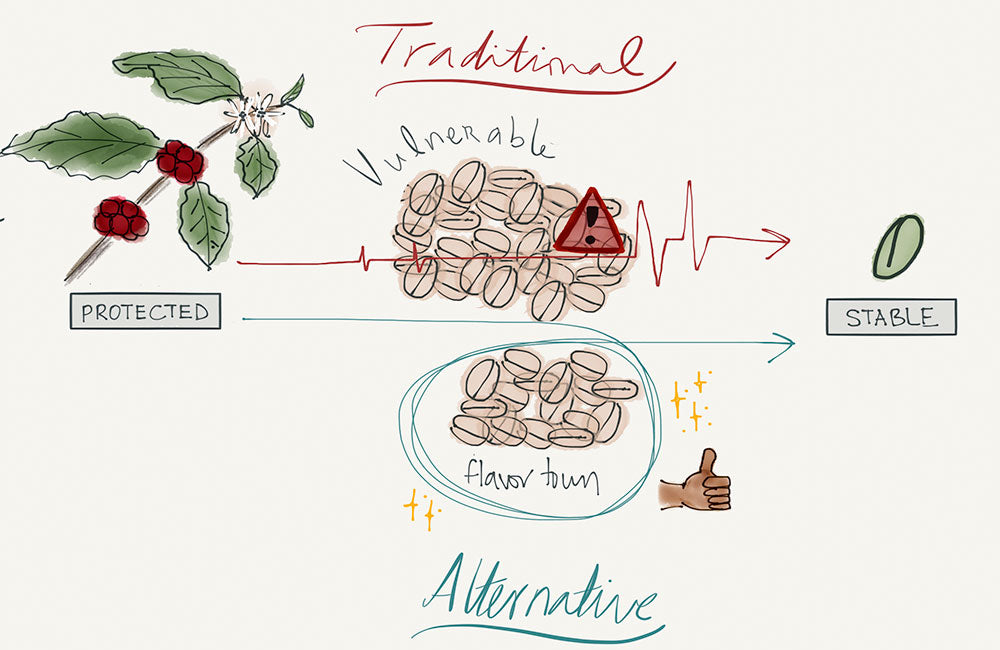

El sector del café define el “proceso” o “beneficio” como el periodo entre la recolección de la cereza y su traslado para secarla, ya sea la cereza entera (vía seca o proceso natural) o el pergamino (proceso lavado). La piel de la cereza sirve de barrera de protección a la semilla. Por eso, cuando se retira, la semilla corre el riesgo de estropearse. La mayoría de las publicaciones al respecto destacan la importancia de acelerar el proceso para reducir la probabilidad de dañar o reducir la calidad del café. Ampliar el tiempo hasta que la cereza llega a transformarse en una semilla seca se considera arriesgado en términos de calidad. Es decir, el paradigma tradicional sugiere que la fermentación no ofrece opciones para mejorar el sabor, solo riesgos. Tradicionalmente, el paso de la cereza de café al café verde seco estaba plagado de riesgos. La creencia popular se ha centrado en limitar al mínimo el tiempo de fermentación para reducir la vulnerabilidad de la semilla. Un método alternativo consiste en controlar y extender la fermentación para obtener atributos de sabor positivos mientras se mitiga el riesgo.

Tradicionalmente, el paso de la cereza de café al café verde seco estaba plagado de riesgos. La creencia popular se ha centrado en limitar al mínimo el tiempo de fermentación para reducir la vulnerabilidad de la semilla. Un método alternativo consiste en controlar y extender la fermentación para obtener atributos de sabor positivos mientras se mitiga el riesgo.

Tradicional: Tradicional / Alternative: Alternativo / Protected: Protegido / Stable: Estable / Flavor town: Universo de saboresAunque los microbios no se pueden observar a simple vista, sabemos que influyen en el sabor y el aroma porque nos damos cuenta de su impacto cuando la fermentación sale mal: lo notamos a través de los defectos en taza. Esto explica el impulso que algunos expertos como Sivetz y Flavio Borem están dando a la retirada mecánica del mucílago. Según este enfoque, el procesamiento mantiene, como mucho, la calidad inherente de la fruta. Los metabolitos del sabor son, básicamente, pedos de bacterias y levaduras. ¿En cuál preferirías marinar tu café?

Los metabolitos del sabor son, básicamente, pedos de bacterias y levaduras. ¿En cuál preferirías marinar tu café?

Coffee marinating in microbe farts: Café marinándose en pedos de microbios

¿Pero cuáles son las ventajas? Sabemos que el proceso puede afectar al sabor de formas positivas o interesantes: esto explica la ubicuidad de los cafés de beneficio honey y la presencia de cafés naturales en la oferta cafetera. Es decir, somos conscientes de que los cafés naturales no saben igual que los lavados así que, claramente, el proceso influye en el sabor, más allá de que haya gente que rechace todos los cafés procesados con un método concreto.

Los productores pueden seguir confiando en la suerte o aprovechar el poder de los microbios que influyen en los sabores en taza. No nos dejemos arrastrar por el miedo: el hecho de que más productores seleccionen sus microbios no significa que los sabores del café se homogenicen. El varietal, el azúcar y los niveles de nutrientes de la fruta, la forma y el material del depósito, la temperatura ambiente, la calidad del agua, la duración del tiempo de contacto y otros factores seguirán afectando a la fermentación. Esto significa que no eliminamos la diversidad de sabores sino que limitamos la presencia de sabores no deseados.

Rechazo la opinión de que el proceso consiste simplemente en mantener la calidad o reducir los defectos. Creo que existen prácticas, como la fermentación controlada, que pueden mejorar y añadir valor al café. Si el café se fermenta de la forma adecuada se convierte en un producto más complejo y valioso que aquel cuyo mucílago se retira mecánicamente. Básicamente, la fermentación transforma la materia prima creando nuevos sabores.

Como los maestros cerveceros, en lugar de esperar un año con un barril abierto expuesto a las condiciones ambientales y no tener claro si el resultado será una delicia o sabrá agua de cloaca, los productores pueden aplicar a su café un método como el kettle sour y obtener los mismos sabores de manera uniforme. Usamos los microbios para romper los nutrientes del mucílago y producir los metabolitos deseados. Elaboramos un “mosto” delicioso y dejamos que el café repose en él más allá del punto de “fermentación” tradicional para que la semilla absorba el mosto y esos sabores. Una selección cuidadosa de los microbios puede proteger el café para que no se estropee y preseleccionar los productos metabólicos que queremos: los que saben y huelen bien.

Controlar la fermentación resulta clave para aprovechar el potencial del proceso y obtener atributos positivos. La fermentación, un mecanismo biológico que ocurre en todos los tipos de procesos, nos da la oportunidad de influir en el sabor, y todos los pasos que van desde la finca al patio pueden impactar en la calidad y uniformidad del café. Al entender el poder de la fermentación y el proceso, los productores y tostadores pueden garantizar la diversidad de sabores mientras mejoran la uniformidad y la calidad del café.

Para ver las fotos sobre procesamiento de café de Lucía, visita su cuenta de Instagram @lluciasolis

Sobre Scott Rao

Scott Rao es uno de las figuras prominentes en el mundo del café de especialidad. Es autor de varios libros, como “Manual del Barista Profesional”, "Everything but Espresso" y “The Coffee Roaster’s Companioin” escritos con la intención de ayudar a la industria a pivotar hacia una forma de entender el café más formada y científica. Gran parte de su tiempo la dedica a la consultoría de tostadores de café alrededor del mundo, impartir clases sobre el tueste de café y en diseñar equipos de café de última generación.

En Ineffable Coffee llevamos trabajando con Scott Rao desde 2018. Ha sido invaluable poder contar con su consejo y experiencia a través de los años. Fruto de esta colaboración nos alegra poder ofrecer este contenido en español.

Artículo escrito por Scott Rao, originalmente publicado en inglés en su blog y traducido por Ana Rubio Ramírez de coffeeandtranslation.com